Re-thinking core ideas when teaching phonics!

- The Reading Hut Ltd

- Jul 30

- 3 min read

Why Linking “A” to an Apple May Confuse Learners Later

In many early reading classrooms, children are introduced to the letter a with a picture of an apple or another word with the /æ/. This seems logical. The word apple begins with the /æ/ sound, and it is easy to remember.

But they can't figure out the rest of the word. They can see the /a/ but the /pp/ and /le/ are going to be introduced much further down the learning road!

It's why all the words shown in our Code Level resources can be decoded and encoded with their existing knowledge.

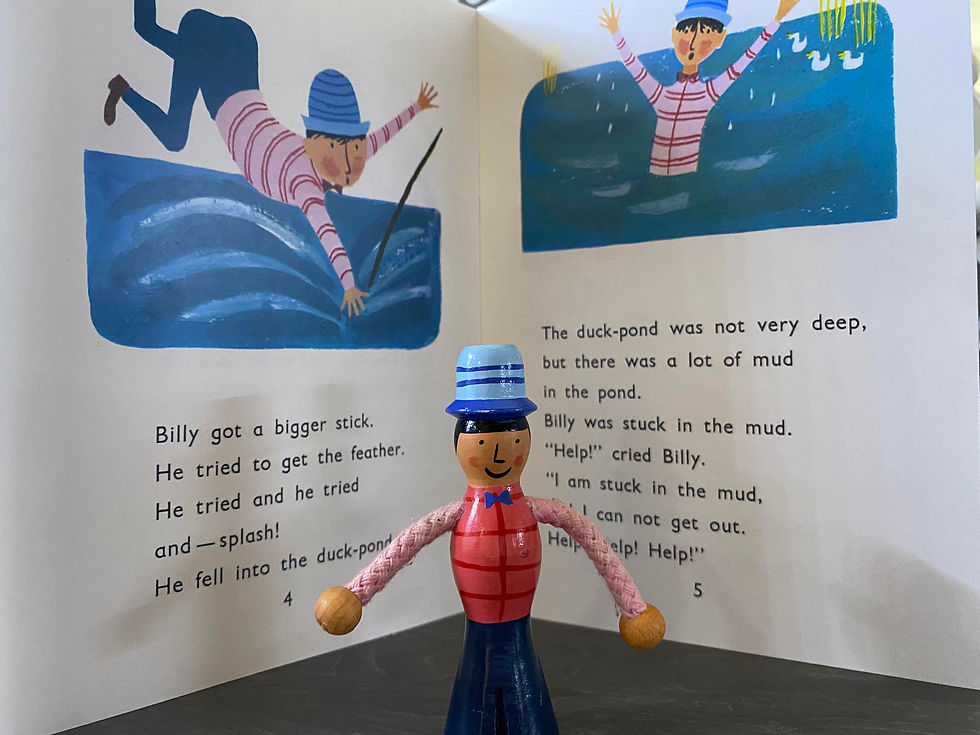

Children may look at the Letterland characters and say the sounds (it becomes a problem if they say "Annie Apple" instead), but this does not mean they understand the link. For example, they may not realise that the focus is on the first sound. If they struggle with phonemic awareness, they are also likely to struggle with blending the target sounds together.

While this kind of image-based cue might offer short-term support, it can create long-term confusion when children begin encountering the same letter in other contexts.

🔍 What does the research say?

Ehri (2003), in a review of phonics instruction research, addressed this directly:

“Some programs, such as Letterland (Wendon, 1992), teach letter–sound associations by embedding letters in characters with alliterative names (e.g., Annie Apple) and stories. However, these associations may interfere with learning because children tend to remember the character and its name but forget the associated sound. Such embedded mnemonics may delay acquisition of the alphabetic principle.” (p. 446)

This is not just about Letterland. Any visual association that links a phoneme to a word rather than to the sound itself risks becoming a crutch that learners must later unlearn.

Why does this matter?

The letter a in English can represent many phonemes: /æ/ in cat, /ɑː/ in father, /eɪ/ in table, /ə/ in sofa, and more. If a child has been taught that a means "apple" and that apple says /æ/, what happens when they try to read any, want, or ball?

They must unpair that initial association and relearn it in new contexts. This is cognitively demanding, even for children like Nicholas who learns easily and doesn't have speech, language or learning difficulties.

A better way: focus on the sound itself

In the Speech Sound Play Plan, children begin by segmenting and blending speech sounds without graphemes. They focus on sounds as abstract units, independent of letters. This builds the concept that words are made of sounds, and even by day 5 they are ready to map them to written symbols.

When graphemes are introduced, children are already tuned in to the sound structure of words. We are introducing them to the concept of "What sound is this a picture of, in this word?" This shift in thinking is vital. In the word 'any' the sound is different.

Why we use Phonemies®

Phonemies® are not words or characters. They are child-friendly phoneme symbols — visual representations of individual speech sounds. They do not rely on a word that happens to contain or start with the sound. Instead, they function like symbolic anchors for the phonemes children are learning to hear, segment, blend and map to spelling.

They help children:

Focus on the speech sound, not the meaning of the image

Avoid semantic interference

Build consistent, transferable knowledge for reading and spelling

In contrast to image cues like apple or Annie Apple, Phonemies® are designed to reduce cognitive load and support easier core code learning, a smooth transition into the self-teaching phase and eventually skilled reading via orthographic mapping!

Comments